reaching the unserved

As we approach the end of our series of public library topics, it's time to return to a topic that you all have touched on during many of your considerations on other public library topics - the unserved.

But first we might ask ourselves who we are talking about when we use that term - the unserved. I did a quick Google search using the terms "public libraries and unserved" and found a variety of understandings of the term. One of the main senses of "unserved" is the lack of a library at all.

- a blog about Indiana libraries used the term to describe communities who don't have a public library in the local area (the issue seems to be related to a plan for library consolidation that may leave out some communities in the process)

- a

1998 fact sheet from the Library Research Service used the

term in pretty much the same way

These individuals are "unserved," as there is no public library legally responsible for meeting their needs for reading matter, information, and access to the "information superhighway."

Other voices highlight "communities" within the community that aren't served the the library as it currently is structured. Many of these "communities" are identifiable by name, if not necessarily by sight. One can class the homeless, the physically disabled, the mentally challenged, the aged and infirm, the housebound into this understanding of the term. There is probably hardly any librarian who does not want to serve these groups, but the realities of money and social policy come into play. Sometimes the state provides the support as does the State of North Carolina in its State Library for the Blind and Handicapped. But sometimes it doesn't.

Many of you all have rightly wondered if the public library can be the last resort to save all the social safety net cases if governments and taxpayers don't want to fund adequate resources for these issues. Can the library be everything to everybody, or should it try to remain true to its historical educational mission? Some would say that more might be done, and that maybe it is part of a library's sense of social duty. But is it?

Speaking of history, the unserved have historically been members of communities not seen as "full citizens." Currently there is a fair amount of effort being made to reach out to immigrant communities, especially the Spanish speaking immigrant community. But one doesn't have to reflect back very far to recall how little served communities of color have been. Clearly there have been gigantic legal and moral changes in this country, but how well are non-white, non-middle class, non-generic communities served by our public libraries?

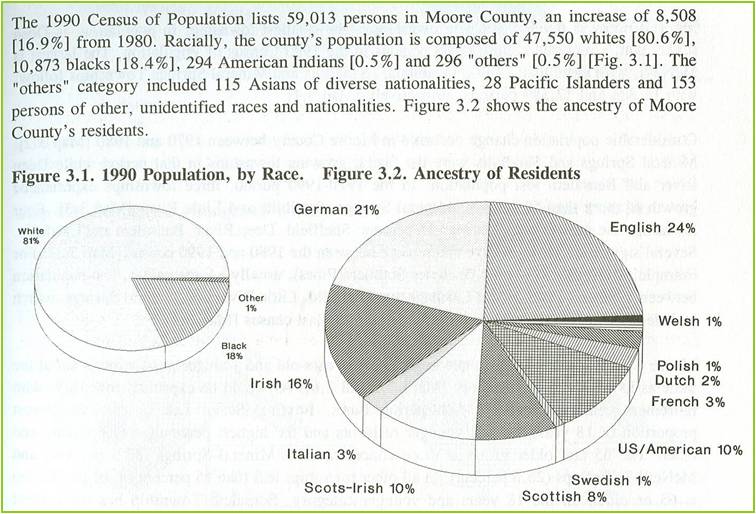

Consider this image for a second. It is from Atlas of Moore County, North Carolina : portrait of an eclectic southern county by Thomas Ross. Written by a professor of geography at UNC-Pembroke and published in 1996, it includes this chart.

Figure 3.1 shows the population of the county by race. The county is mostly white, but almost one fifth of the residents are black. Figure 3.2 is entitled "Ancestry of Residents", but who are the "Residents" whose ancestry is being portrayed? Does one see any indication that the 19 percent of the "Residents" who are other than white are being included?

Now this may well have been a minor and not ill-intentioned oversight on the part of the author and publisher. But what does it say about us?

- Our eyes are open, but do we "see" those who are not like us?

- We think we are fully empathetic, but do we really know those who are not like us?

- Is it a possibility that in our effort to extend library services to all, that we unconsciously forget that we are not thinking about "all of us".

Sometimes those groups that we view, but don't "see; that we understand about, but sometimes forget to consider; are right in front of us. During a discussion about the same topic, a staff member at West Regional Library in Morrisville, NC stated that the most "unserved" group at their library was probably well-educated, high-income, middle-aged white males - if only because the library seemed to be reaching out to everyone but them. The same concept was mentioned in a 2007 article from Library Administrator's Digest - men were the great missing group.

One of you all also identified another group:

Hey! May be I am in an underserved population--educated, 20s/30s, who don't have children, and don't need language and/or computer help.

But these latter two groups are not like some of the earlier ones. They are not limited by financial resources or physical frailties; they have been the ones who benefit from the structure of American society. Should we spend too much time worrying about how well or how ill they are served by the public library?

So, again, what do we mean when we say "the unserved"? It is pretty clear in hindsight and it seems pretty clear when we look for segments of our society that are getting the short end of the stick.

But to reflect back to our initial considerations of the philosophical underpinnings of both "the public library" and "your personal understanding of the meaning of your public library," where should we direct our concerns in the near future?

And, to bring the political context back in again, whose support will we really need in order to be able to secure the funding necessary to reach out to groups in our community who could really benefit from what our public libraries could offer them?

Do we risk selling our souls in order to do good works?

[top]