This report presents the results from a nine-month study of three federal government statistical websites. The study was undertaken from October 1996 to June 1997 under the auspices of the Bureau of Labor Statistics and examined the BLS website, CPS website co-sponsored by BLS and the Bureau of the Census, and the FedStats website sponsored by the Interagency Council on Statistical Policy. The main objectives of the study were to determine who uses these services, what types of tasks they bring to the sites, what strategies they use for finding statistical information, and to make recommendations for design improvements.

Given the range of services and users and the complexity of the human-system interactions such an investigation entails, a multifaceted set of methodologies were used to collect data. These included: reviews of literature and existing websites, site mapping, document analysis, individual interviews and email questionnaires with staff at different government agencies, focus groups with various intermediaries responsible for aiding the public in finding statistical information, content analyses of user email requests, usability tests with representative end users, and transaction log analyses. These methodologies were selectively applied to the different websites. In some cases, they entailed the invention of new data gathering and analysis techniques. Taken together, the methodological retinue provide an exemplar for agencies to adopt for ongoing application to monitor, maintain, and evaluate their online information services.

Users

A wide variety of user types for the sites were identified. These were:

business users,

academic users, the media,

the general public,

government users,

education (K-12) users,

statisticians, and

users in libraries/museums and other non-profits.

Tasks

Users bring a wide variety of statistical needs to these websites.

By integrating results from the different data collected, a multidimensional

task/question taxonomy

was developed.

The pragmatic (contextual) dimension includes attributes in three categories:

-

goal (learn,

verify, judge, explore, refer, subtask, ongoing, plan),-

constraints

on the task (time, volume, geographic location), and-

system (database

match to task, search and extract tools, formats, entry point and path).

The semantic dimension includes attributes of topic, level of abstraction,

level of specificity, and number of facets.

The syntactic dimension includes attributes in three categories:-

expression type

(what, where, who, how, and why), -

goal type (closed,

interpretive, accretional), and -

specificity

of expression.

Strategies

Results are based mainly on transaction logs for the BLS site.

Many users abandoned their session after one or two requests.

Users were found to be mainly purposeful in their information seeking

and strongly guided by the organization of the website.

There were differences in how some classes of users conducted their

sessions with more sophisticated users , especially those from .GOV and

.COM

domains, conducting longer, more frequent sessions using more data-rich

information services.

Design Recommendations

A variety of specific design recommendations are made in the report.

The most general recommendations for all sites include:

add vocabulary clarification features such as authority lists, query

expansion, thesauri, and spell checkers;

consider some specific reorganization based on project results, e.g.,

A-Z list in Fedstats, moving Occupational Outlook Handbook higher in the

BLS organization, and emphasizing timely data releases on the home

page;

consider using the task taxonomy as a template that guides user interaction;

consider developing alternative interfaces that users may adopt to

suit their needs; and

develop systematic help, FAQ, and tutorial modules for sites.

Policy Recommendations

In addition to these results, several general agency organizational

observations and recommendations surfaced during the study. Most generally,

agencies should:

develop suites of evaluation techniques, tools, and procedures that

are regularly applied and used to guide site evolution; and

agencies should develop and publicize policies for collection development

and public access and support for the various websites and other online

public services.

These recommendations should be part of efforts to manage change as

the online information services change and concomitantly change the agencies

themselves.

In the summer of 1996, Gary Marchionini (University of Maryland) and Carol A. Hert (Indiana University) were invited by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Office of Research and Evaluation to undertake a 9 month (September 1996 - June 1997) investigation and evaluation of several websites provided by and/or sponsored by the Bureau. These sites are:

Each of the sites was developed with a particular goal. These are:

BLS:The primary user of the BLS site is someone who knows or believes BLS has statistics relevant to their needs. The site should meet the needs of external users.

CPS:As defined in the late 1980's, the original goal was to provide BLS and Census staff access to all the micro-, macro-, and metadata associated with the CPS production process. The site is now geared more towards the external rather than the internal customer.

FedStats:The site should provide entry to statistics produced by about 70 Federal organizations covered in the OMB report on the budget for Federal statistics. The primary users are people who do not know which agencies have statistics relevant to their needs.

During the first meeting in October 1996, preliminary goals for the project were established. BLS staff expressed an interest in understanding how people were using the various sites, including their tasks (or goals) and their strategies for moving about the sites. Arising out of these discussions were the following specific questions which were to guide the analysis:

1.What categories of information seekers use the sites?

2.What are the tasks (or goals) in which these information seekers

are engaged?

3.What strategies are employed by information seekers as they use the

site?

4.What are the design implications for the sites of answers to the

previous questions?

Several of these terms need definition in the context of this study

as they are often used interchangeably in the information science literature.

The broadest "information seeking unit" we discuss is an information need.

Thus a person who may be making a decision to relocate and decides to look

for information on various cities is engaging with an information need.

The task is a specific action taken in support of that information

need. Thus the decision to look for the CPI for various cities is a task

associated with the relocation information need. The goal is the

expected (or hoped for) outcome of the task. Thus the goal of looking for

the CPI

for several cities is the set of CPI's for the cities. A strategy

is a plan for action, these may be both mental (such as top-down problem

solving) and system oriented (starting with keyword searching). Strategies

are executed via tactics and moves which are the actual discrete

behavioral actions of a user on the system (such as pressing a key). Presumably,

when the goals are well-matched to the information need, the task is appropriate

to the resources and user abilities, and the strategies are well-executed,

then the information need will be met.

Our purpose in this study was to provide additional theoretical insight into the design and evaluation of Websites, in particular, those providing statistical information and associated information. The study team also found the focus on information seeking to be theoretically interesting as the connection between information seeking strategies and system design implications, particularly in the area of statistical information, is under-developed. A literature review found only 1 study (reported in Robbin and Frost-Kumpf, 1997; and Robbin, 1992) which described empirical work in this domain (See Appendix 1-1).

1.3 Overview of Study Activities

The goal of the first several months of the project (through January 1997) consisted of the development, on the part of the study team, of a rich understanding of the three sites and the context in which they existed. This led into the specification of the methodology to be employed during the remainder of the project. The study methodology evolved throughout the project as additional insights were gained by the study team of the nature of the sites and the needs of the agencies. The methodologies developed as a result of the project are themselves important contributions to the continued development and management of the three websites. The final set of data collection activities are described in Section 2 of this report.

Activities engaged in during the early months included literature searching, reviews of other statistical websites (see Appendix 1-2), interviews with selected BLS staff, gathering of mission statements for the sites, and ongoing discussions among the study team as to how best to gather data and divide the work. As a result of these discussions there began to be distinctions made between the BLS and CPS sites and the FedStats site due both to their differing maturity levels and primary missions and somewhat different methodologies were decided on for the sites. At the January 13, 1997 meeting, these preliminary methodologies were proposed, modified upon comment from BLS staff and the FedStats taskforce, and a revised set of data collection and analysis activities provided.

Some data collection activities were started during the early period of the study but most reached full swing during the period January - May 1997. A report of the status of the various activities (and some preliminary findings) was provided during the May 6, 1997 meeting and approval provided for the final report structure and reporting mechanisms.

The project goals concerned complex systems and processes and all participants agreed that a variety of methods and approaches were necessary to address these complexities. Thus, a multifaceted investigation was undertaken that included a variety of data collection techniques and an ongoing triangulation process that integrated the different data to address the research questions. In some cases, new methodological procedures were invented and the explication of an overall evaluation suite is itself an important deliverable for the project.

A multifaceted approach to web usability testing was also a strong theme adopted at the ACM SIGCHI Workshop (March 23-24 in Atlanta) for which the project team prepared a position paper describing our approach (http:www.acm.org/sigchi/webhci/chi97testing/). Such an approach has been used successfully in evaluating other complex systems and processes (e.g., Marchionini & Crane, 1993; Harter & Hert, 1997; McClure, 1997) and is analogous to a medical CAT scan where diagnosticians collect data on multiple views of the organ of interest, and aggregate and integrate these views into a diagnosis. One important distinction in the methodology used here is that the views use different data collection techniques rather than one technique applied successively. A second important distinction from a CAT scan is that these methodologies are applied repeatedly over time as an ongoing part of the development and maintenance of the online services.

There was an investigative phase (October, 1996-January 1997) during which time we worked to clarify the research issues and understand the websites and respective government organizations. For this phase, we used five data gathering methods: literature and website reviews, expert critiques of the websites, site mapping, document analysis, and interviews (personal interviews with BLS and Census personnel working with the BLS and CPS sites, and electronic questionnaires with the Interagency Council on Statistical Policy Task Force responsible for the FedStats site (referred to in the remainder of the report as the FedStats task force) and support staff in statistical agencies contributing to FedStats).

The second phase of the project focused on data collection based on user activities: online interviews and focus groups (for FedStats), content analysis of email requests (for BLS/CPS), impressionistic analysis of online comments (for FedStats), usability tests (for FedStats), and transaction log analyses (for BLS/CPS). In some of these cases, new data collection and analysis techniques were devised.

The study team brought a broad range of methodological expertise to the project and thus was able to significantly extend the data collection activities beyond those generally employed in Website analysis and evaluation. Most Website evaluation activities have employed either usability testing or transaction log analysis or both in tandem (e.g., see various position papers at http:www.acm.org/sigchi/webhci/chi97testing/). We also built upon the April 1996 usability study conducted by and Fred Conrad and Michael Levy for the CPS site. We employed these as well but extended our data collection activities to include several not normally employed including content analysis of email messages, focus groups, and a variety of interviews.

Transaction logs are automatically captured by the Webserver and thus are readily available for analysis. In this study, the team made significant enhancements to typical analyses (these are reported below). Transaction logs provide information about the pages accessed by users, information which provides some guidance for answering Research Question 2. Additionally, we were able to map "paths" through the site which provided information associated with Research Question 3.

Usability testing is often employed in Website design and evaluation (as in other interactive systems) as the investigation of people using the system often leads to insights about aspects of the design that expert designers may not have gathered. We therefore chose to do some usability testing, particularly for the FedStats site, where the design was still emerging and early usability testing might lead to significant changes in site design.

The study team would have been remiss to not take advantage of human expertise resident in the various agencies. The BLS and the other FedStats agencies have a long tradition of public service which has involved answering mail, telephone, fax, and in-person queries. These experts were useful sources of information about the types of users they had helped in the past, what types of queries those users brought, and how the experts themselves had helped them (which provided insight into strategies and system design). Thus the study team identified several populations of staff involved with helping the public, as well as several other staff with a stake in the various sites (such as the FedStats Task Force).

These experts preserve some of their communication with these users. Email messages to the BLS Labstat email address are routinely saved. Analysis of email messages enabled us to look at the content of users' queries which provided yet another vehicle for developing a taxonomy of user tasks on the sites. With the official "opening" of the FedStats site in late May 1997, online comments from that site have also become available.

The BLS and other agencies also have an interest in expanding their services to new populations of users. In order to understand the needs of these sets of users (and gather additional information on current users), it was important to speak with users. Since the user communities (actual and potential) constitute the population of the United States and beyond, the study team identified types of intermediaries (e.g., librarians, teachers, statistical consultants) who help the larger population locate, access, and use statistical information. These intermediaries were likely to have information about tasks and strategies aggregated from the users they have served.

Table 2.1.1 summarizes the data collection activities of the study.

(INSERT TABLE 2.1.1)

2.2.1 Expert critiques. We systematically examined the three web sites for two purposes: first, to become familiar with the content and structure of the sites; and second, to make suggestions for improving the sites. The products of these activities were site maps and various specific recommendations related to screen layouts and site features and organization. We sometimes used personally constructed scenarios (e.g., explain what the geometric mean formula means for the CPI; what is the unemployment rate for Hispanic Americans in Arizona) and sometimes reconstructed sessions logged by the server.

2.2.2 Interviews. We conducted two types of interviews. First, we interviewed analysts and help desk personnel at BLS and Census. For this purpose, we created an interview protocol that guided questions in the following categories: Content/Context of the service, Users, Strategies (those used by both staff and by users), and Other (see Appendix 2-1). Eight people were interviewed using this protocol. Two interviews were conducted in person and six were conducted over the phone. Interviews typically lasted one hour and in four cases more than one of the research team members participated in the interview. Notes from the interviews were emailed to the participants for verification and clarification.

The second type of interview technique took the form of email questionnaires and was applied to two groups of people responsible for the FedStats site. FedStats became publicly available on May 22, 1997. Prior to that time, it was available in prototype form and could be used by only those who knew the URL for the site. Due to the very limited number of users, we relied heavily on the expertise of the FedStats Taskforce, and on the experience of staff in the participating FedStats agencies. The experiences and perceptions of these groups were solicited via electronic questionnaires.

A questionnaire was sent to the FedStats task force in January 1997 via the FedStats electronic mailing list. All members of the task force responded to the questionnaire (see Appendix 2-2), though two members reported that they did not have public service responsibilities or were on the task force for reasons not related to public service and so did not supply answers. Five usable questionnaires were received and tabulated. Since all responses were open-ended in nature, answers that seemed significantly similar were grouped together.

A questionnaire similar to that employed in the BLS interviews was developed to send to help staff in various agencies (See Appendix 2-3). These staff were identified by members of the FedStats task force. The questionnaire was electronically distributed to these staff using individual email addresses. 15 questionnaires were sent, 11 were returned. One reminder was sent to the non-respondents but no further surveys were received. Agencies represented in the returned questionnaires were: Bureau of Economic Analysis (2), Bureau of Labor Statistics (3), National Science Foundation (3), and the National Energy Information Center (3). The returned questionnaires were tabulated. Since all responses were open-ended in nature, answers that seemed significantly similar were grouped together.

2.2.3 Focus Groups. Focus groups are group interviews with 5-10 participants in which a topic is explored (the focus) by the participants (Kruger,1994). They have been widely employed in settings where the phenomenon is not well understood because the respondents can offer information and/or move the discussion in directions not predetermined by the researcher. In exploratory settings, a predetermined questionnaire may miss valuable insights. Additionally, they are most appropriate in situations where group learning or group attitude forming is appropriate. For example, focus groups have been used widely in marketing surveys because consumer buying preferences are shaped by group perceptions of products. A focus group is facilitated by the researcher who asks some opening questions and keeps the discussion focussed on the topic at hand.

Findings from focus groups are qualitative in nature, providing rich pictures of the phenomenon as experienced by the participants, but do not yield generalizable results both due to the unrestricted structure of the discussion and the tendency to have non-random selection of participants. Our employment of focus groups in this study was predicated on several conditions: the exploratory nature of the project, the desire for respondents to learn from and be exposed to the ideas of other participants, and the need to reach a number of people in a short space of time.

Three focus groups were held in Bloomington, and Indianapolis, Indiana during April 1997. A total of 19 respondents participated. (See Table 2.2.3.1 Focus group participants were identified through contacts provided by members of the FedStats Task Force. An effort was made to reach a wide range of participants who provided data to constituent groups. Some participants were active data users themselves. The focus questions were:

What is your role in helping people find federal statistical information?

What types of questions do the public ask about federal statistics?

What tasks lead the public to ask for federal statistical information?

What types of information or data do you provide to the public in response

to these questions or tasks?

How do you help people find statistical data now?

How do you think people go about finding statistical data on their

own?

How might a Web-based service (such as FedStats) affect how people

find statistical information?

What else is important for us to understand about the public's use

of federal statistical information?

In a focus group, the interviewer uses the questions as probes but allows respondents to take the discussion in other directions. Therefore the questions above represent a general sense of the topics covered during the focus group interviews rather than the only questions asked.

TABLE 2.2.3.1 FOCUS GROUP PARTICIPANT SUMMARY

Focus Group 1 (April 10, 1997, Indianapolis, IN.): 8 respondents

3 researchers/analysts from a university-sponsored urban/economic

analysis planning institute that focusses on regional issues,

director of information services at a statewide business data center,

librarian at the statewide Chamber of Commerce,

economic analyst with a large Midwestern bank's economic research department,

analyst at state government economic division

Focus Group 2 (April 16, 1997, Bloomington, IN.): 6 respondents

research analyst in a social science data center for university

affiliates (students, faculty, etc.)

head of Public Services at a public library

university government documents librarian

university librarian who works with students in education and also

directed a project to make social science data (including Census) available

via the Web

analyst with Indianapolis city planning department

analyst with university-sponsored survey research center (specialist

in sample selection)

Focus Group 3 (April 17, 1997, Indianapolis, IN): 5 respondents

analyst in statewide economic development agency

public librarian in Business/Economic division of large urban central

library

analyst at statewide business data center

government documents librarian at the State Library

analyst for the research and planning arm of United Way of Indiana

2.2.4 Content Analysis of Email. BLS receives hundreds of email requests per month from users. These requests come to the LabStat help desk and to individual analysts in various BLS departments. These requests provide insights into the kinds of problems users have with the system and the kinds of statistical problems they bring to the websites. Although it is important to keep in mind that the email requests represent a self-selected sample of the overall user population, the volume of requests and variety of topics and expertise make this sample particularly valuable for answering the project research questions. Content analysis is a methodology that seeks to find patterns in textual data (e.g., Holsti,1969; Krippendorf, 1980). For the purposes of this project, a content analytic strategy for electronic mail messages was developed and tested.

In this study, we were able to gather 2 months of messages sent to the BLS Labstat email address. We also received a smaller set of messages (Sept. - Nov. 1996) which had been received by the CPS helpdesk staff. The CPS messages were analyzed first, and a coding scheme was inductively derived from those messages (see below). This coding scheme was then employed (with minor modifications) to code the BLS data. Summary information about the messages is found in Table 2.2.4.1.

Table 2.2.4.1: Email Summary Information

Number of

Email Source Date Number of Messages Questions

CPS Sept.-Nov. 96 90 126

BLS Labstat Nov. 96 379 657

BLS Labstat March 97 569 827

The study team inductively derived a content analytic coding scheme for the email message content. An inductive strategy is useful in situations where no taxonomy exists prior to analysis, as was the case here. There is limited guidance available in the literature about how queries concerning statistics and associated information might be categorized. The scheme development process followed general principles provided by Krippendorf (1980) and Holsti (1969). As messages were read, categories were preliminarily developed. After the analyst had a sense that no new categories were being added to the scheme, the preliminary scheme (and associated coding rules) were formalized. A second analyst then received the scheme and both analysts coded the same subset of the messages (10% of the sample). Coding decisions were jointly reviewed to confirm that the scheme was detailed enough for any coder to reach the same decision about codes for a message as any other coder.

Several statistics are available to verify that coding agreement is due to the reliability of the coding scheme and not random chance. We used Kappa (Cohen, 1960), a statistic which considered the number of decisions made and the expected occurrence of agreement if chance alone was operating. At the point our kappa was tabulated, our value was .71. A value of .6 or higher is generally considered sufficient to indicate that chance alone is not accounting for the agreement. With this level of agreement, the messages were divided between the two coders, who then went through all the email messages and tabulated instances of various codes.

The coding scheme employed is indicated below (Table 2.2.4.2). It has two dimensions which were coded for each question in a message. (Some messages had more than one question and each question was coded separately.) In all cases, it was the correspondent's language that was used. For example, the coders did not attempt to infer whether a person asking where a particular data item was actually was asking for the number itself as there was no way to assess that distinction.

The first dimension captured the content of the question. The second dimension captured the nature, or strategy of the query. Both dimensions are necessary to understand the nature of a particular question. A tabulation matrix (presenting in the findings sections of the report) was developed with content type on one dimension and strategy/question on the other.

TABLE 2.2.4.2: Email Coding Scheme

Date of Finalization: 13 March 1997

Authors: Carol A. Hert, Kim Gregson, Anita Komlodi

I. Content Dimensions

This dimension describes what type of information the user requested

System: the website itself ( as opposed to the ferret search tool on CPS, for example, which goes under tools). This category includes questions relating to how the website is organized/structured.

Data: question related to actual values of variables or for actual information (such as, "I need information on the economic outlook for Atlanta")

Methods: anything related to how the data were collected such as how many surveys were conducted, as opposed to metatdata which would be information about the meanings of variables, codes, etc.

Metadata: information about the meanings of variables, codes, etc.

Tools: tools for data manipulation, such as ferret, available on the Website

Publication: BLS information in paper form (whether it is stats, methods, etc.)

Costs: questions relating to how much things cost (such as "how much would it cost me to get data on...")

Other

II. Strategy/Question Type Dimension

This dimension describes what the user wants to know about the information they indicated and what form the question took (strategy).

What: content/definition of

How: process

When: time of

Where: location/access to, including directions to answer questions such as "can you direct me to...", use only when they explicitly ask about location as opposed to existence or that they can't find something

Do you have - existence of

Is it an error

Why: rationale for something

Who

Other

Coding Rules:

Code all questions in each email. Code at the sentence level, thus if a respondent says "I need data on x statistic. Can you tell me where to get this", code this as 2 questions: a what/data and a where/data. However, if a respondent says, "I need data on x statistic, y statistic, and z statistic. Where can I get access them?" it would get coded as only 2 questions: a what/data and a where/data. Multiple examples of types of data should not be coded separately.

Code each question on both dimensions (content & strategy/question type).

Use the respondent's language to help determine which type of question it is.

On the coding sheet, each email message should be listed by email address. If there are multiple questions within each email, they should be numbered consecutively. Thus if Smith had 4 questions, the coding would be Smith 1/4, Smith 2/4, etc.

Some messages are not about any data or publications available from BLS. For example, if a message gives the user's resume or describes a new business site, code those as Other.

2.2.4.1 Further Analysis of Email. After coding and tabulating the 2 sets of BLS messages, it was apparent that only a few categories had large numbers of questions associated with them. These were: what/data, where/data and do you have/data. A second content analytic scheme (Table 2.2.4.3) which was more specific than the first was developed in order to gain a more detailed understanding of the nature of these numerous questions. We were interested in knowing whether particular statistics or types of statistics were frequently requested--what in particular were people asking for? An answer to that question might suggest some particular design recommendations for index or button choices. (For example, if most questions asked for the CPI, it might be useful to place a link to the appropriate table on the BLS homepage.)

The second scheme was also inductively derived as described above. The two analysts had 90% agreement in their coding choices in the subset of questions coded and thus the scheme was finalized as it appears below. Again there are two dimensions. The first is the content dimension: what type of statistic is being asked for. The second dimension captures characteristics of the data requested. Three characteristics were indicated by requesters: regionality, time, and amount (or number) of statistics wanted. (These dimensions were also suggested by focus group participants as being important.) An analyst coded all questions which fell into the what/data, where/data, and do you have/data categories.

Table 2.2.4.3 Coding Scheme for "Data/What" Email Questions

Date of Finalization: 16 May 1997

Author: Kim Gregson

I. Content Dimension

These are specific statistics, such as the CPI and PPI, as well as general topics that are most often asked for.

Employment/Unemployment : e.g., # of employees, employment rates, job qualifications and outlooks

Productivity: any measures of productivity such as work stoppage, job retraining, time lost to work accidents, # on the job injuries, absenteeism

Compensation: such as average salaries, salary ranges, comparative salaries, income of business owners, fringe benefits, effects of education on salary

Prices: cost of living, historical survey of prices, national inflation rate

Federal Government Related: effect of defense spending cutbacks, money spent by government agencies, government related requests that do not fit into any of the other categories

Demographics:

CPI: (note: CPI and PPI were coded separately due to the frequency of requests in the data set)

PPI:

Other:

II. Specificity Dimensions (pick one from each of the following dimensions)

These are ways people make their data requests more specific.

1. Time (if not given, code most current)

most current: latest, this year's, this quarter's, most recent

series: for a range of dates, for a time series

historical: one specific time in the past

2. Location (if not given, code national)

city: city, county, local, MSA, multiple cities for comparisons

state: a specific state

region: multiple states, general regional description such as

the Southwest

national: US as a whole

international: specific countries or continents

3. Amount (if not given, code one)

one: a specific statistic, even if it is in a request for a

time series

Code only messages that were coded as data/what in a previous

coding pass.

Code all requests for data in each of those messages.

For each request, code four pieces of information - one content description, and each of the three aspects of the specificity dimension: time, location, and amount. Examples are provided for each choice.

Use the respondent's language to help determine which type it is.

On the coding sheet, each email message should be listed by email address. If there are multiple questions within each email, they should be numbered consecutively. Thus if Smith had 4 questions, the coding would be Smith 1/4, Smith 2/4, etc.

2.2.5 Usability Tests. Usage of the FedStats site was investigated during a series of usability tests held in Bloomington, IN and Washington, D.C. Three tests were held. The structure of each test was as follows. A group of users (ranging in size from 4-7) explored the system simultaneously (each person at a computer) for approximately an hour (see Table 2.2.5.1). Subjects were paid for participation in the tests. The exploration was guided by two scenarios designed by the research team and one scenario developed by each individual. Scenarios are a widely used strategy for usability testing (Carroll, 1995). They enable both a somewhat structured experience (so that researchers can have respondents experience the parts of the system in which researchers are particularly interested) as well as allowing flexibility for respondents to employ their own choice during system use. The scenarios used in this study were as follows:

1.You're writing a newspaper article or letter to an editor and you need the latest figures on average weekly earnings for blacks and whites to make a point. You also want a clear definition of just how unemployment is defined.

These scenarios were designed to investigate the functionalities of the FedStats site rather than those of the sites of the individual agencies. As FedStats' primary purpose is to support the location of statistics and associated information, the predetermined scenarios focussed on tasks involving statistics location rather than statistics use.

Respondents were instructed to write down their "answers" on the sheets describing the scenarios for further analysis by the research team. In addition, they were asked to use the Bookmark function of Netscape to indicate pages that were particularly helpful during their explorations. Unfortunately, due to the use of frames in the FedStats site, the bookmark files were not usable. In frames, what gets bookmarked is the frame itself rather than the page in the frame.

Following the system explorations, the respondents completed a short questionnaire (Appendix 2-4) designed to capture some demographic data as well as a variety of summary satisfaction measures. These measures were based on measures from the validated survey: University of Maryland Questionnaire for User Interaction Satisfaction (Chin, Diehl, & Norman, 1988). The session concluded with a group interview of approximately one hour to one hour and a half with the purpose of debriefing the respondents on the experience. The following types of information were solicited:

How did respondents go about answering each scenario?

What strategies did respondents employ to work through the scenarios?

What factors (system, personal, etc.) influenced the respondents' perceived

successfulness?

What helped the respondent accomplish the scenarios?

What hindered the respondent from accomplishing the scenarios?

How could the OSS site be changed to increase the respondents' ability

to use it successfully?

What kinds of questions do they think the site in its current form

would be useful for answering?

How could the homepage (and top level) OSS pages be organized to increase

a user's ability to use the site successfully?

What else is it important for us to know to understand how they used

the site during this session?

Would they ever use this site again?

Table 2.2.5.1: Usability Test Summary

Bloomington, Indiana: 28 March 1997 with seven participants.

- database manager

- graduate student/assistant instructor

- graduate student

- sociology graduate student

- graduate student

- non-degree international graduate student

- graduate student/associate instructor

Washington DC: 19 May 1997 with four participants.

- senior Biology major

- senior Physics and Music Composition dual major

- first year Law student

- senior in joint BBA/MSIS program

Washington DC: 27 May 1997 with six participants.

- political management graduate student

- Civil Engineering graduate student

- MBA, just graduated

- doctoral student, on leave from position as school teacher

- junior, political communications

- third year Law student

2.2.6 Transaction log analyses. Web server software routinely log every request for information. The BLS site receives approximately one million "hits" (requests to the server) per month and the resulting server logs contain hundreds of megabytes of data each month. These data are appealing because they represents the activity of the entire population of users each month rather than the more typical samples of activity other data sources provide. Throughout the computing community there is a long history of interest in log analysis from multiple perspectives: improving web site design and services (e.g., Nielsen; CHI workshop position papers); studying user information-seeking behavior (e.g., Penniman, 1975; Lin, Liebscher, & Marchionini, 1991; Rice & Borgman 1983; etc.); and maximizing sales or coverage (e.g., http://www.doubleclick.com). The growth of web sites has raised this interest to new levels. There are several challenges to such analyses.

First, transaction logs for popular sites such as BLS are very unwieldy to process. The sheer volume is an impediment since it is impossible to manually process the data (e.g., printing out one month of BLS logs would take about 100,000 pages of paper). Programs must be developed and tested on subsets of data for verification.

Secondly, server logs provide an incomplete trace of each user's behavior. For example, users may jump to other sites between any BLS access and during a session may return multiple times to BLS pages already visited but these additional uses are not recorded in the server logs since the user's browser typically caches page information once it is transferred (such caching will also tend to make popular pages under-represented in the transaction logs). Furthermore, other levels of caching such as institutional or regional systems may exacerbate this problem. Additionally, other client-side behavior (e.g., mouse movement) is not included. Thus, the server logs do not offer a complete trace of user behavior.

A third challenge is distinguishing users. The logs are created on the fly and in any given minute, hundreds of requests may be logged between a single individual users' successive requests. The logs must be segmented into user sessions. This problem is complicated by the identification used in logs. The requesting machine name (IP address or DNS name) is used as the request ID. A machine may truly be an individual's machine and thus represent a single user or it may be a laboratory machine shared by many students or employees, or a proxy machine that handles all WWW activity for a company or agency. Thus, a scheme for segmentation must first be determined and even after the logs are parsed into sessions it is likely that some sessions represent multiple users.

Although these are significant challenges, we believe that systematic processing and targeted data mining offer valuable insights into how users work in a website. We took two approaches to transaction logs in this project. First, we examined the summary reports that BLS produces each month. Second, we examined individual user sessions as sequences of events and did a sequential analysis for overall usage patterns as well as for specific patterns of use.

2.2.6.1 Logs and BLS summary reports.

Standard server logs consist of entries such as this:

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:51:54 -0500] "GET /blshome.gif

HTTP/1.0" 200 45725

205.167.6.186 - - [02/Nov/1996:09:51:55 -0500] "GET /oco/ocoban.gif

HTTP/1.0" 200 17795

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:06 -0500] "GET /cgi-bin/imagemap/blshome?109,187

HTTP/1.0" 302 57

205.167.6.186 - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:06 -0500] "GET /surveys.gif HTTP/1.0"

200 1374

205.167.6.186 - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:06 -0500] "GET /opbhome.gif HTTP/1.0"

200 2418

205.167.6.186 - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:06 -0500] "GET /backhome.gif HTTP/1.0"

200 2277

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:06 -0500] "GET /infohome.htm

HTTP/1.0" 200 833

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:07 -0500] "GET /backhome.gif

HTTP/1.0" 200 2277

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:14 -0500] "GET /infomenu.gif

HTTP/1.0" 200 24576

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:14 -0500] "GET /infoban.gif

HTTP/1.0" 200 18016

cust49.max3.los-angeles.ca.ms.uu.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:20 -0500]

"GET /ceshome.htm HTTP/1.0" 200 2232

205.167.6.186 - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:22 -0500] "GET /oco/oco0002.htm

HTTP/1.0" 200 1641

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:22 -0500] "GET /cgi-bin/imagemap/blshome?121,57

HTTP/1.0" 302 57

uwfts1-7.firn.edu - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:22 -0500] "GET /blshome.html

HTTP/1.0" 200 1036

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:22 -0500] "GET /datahome.htm

HTTP/1.0" 200 3230

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:25 -0500] "GET /backhome.gif

HTTP/1.0" 200 2277

cust49.max3.los-angeles.ca.ms.uu.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:29 -0500]

"GET /cesban.gif HTTP/1.0" 200 18220

pt48.an4.ameritel.net - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:33 -0500] "GET /databan.gif

HTTP/1.0" 200 17585

uwfts1-7.firn.edu - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:36 -0500] "GET /blsban.gif

HTTP/1.0" 200 21016

www-r9.proxy.aol.com - - [02/Nov/1996:09:52:45 -0500] "GET /news.release/ecec.t06.htm

HTTP/1.0"

Using the first record as an example, the records provide the hostname or IP address (pt48.an4.ameritel.net), the time (November 2, 1996 at 9:51:54 am), the request (an HTML request for the BLS home page), the status code of the request (200 is satisfactory request), and the number of bytes transferred (45725). These log files are very large (the October file was about 200Mb) and represent the 958,887 requests for that 29 day period. These files are the basis for the customized sequential log analysis conducted for this project and described in section 2.2.6.2. Most servers also provide some summary reports that help webmasters monitor and maintain aggregate site activity. BLS staff create the following report files each month:

cgi.txt logs of requests that launch some cgi program on the server. In the December log, this file was 2.4Mb. It contains statistics on the number of requests made that launch cgi programs (e.g., keyword search, selective access, series reports, and most requested series). The frequency of each unique request is contained in the report. For example

0 5 5 /cgi-bin/keyword.pl?Gross+Product+Development

indicates that there were five keyword searches for the term "Gross Product Development" with this exact spelling and capitalization used. None of these requests came from within BLS, 5 requests came from outside BLS and there were a total of five requests.

flat.txt logs of requests through FTP and Gopher sites. These files were not considered in this analysis. For December, this file was 179K.

htm.txt This file contains statistics on the number of requests made for HTML documents (pages). For December, this file was 116K. The frequency of each unique request is contained in the report. For example:

40 1401 1441 /790home.htm

0 1 1 /homepage.htm

The first line shows that 1441 requests were made for the state and area current employment statistics, forty of those coming from within BLS. The second line shows there was a single request for a page that does not exist in the BLS site. It resulted in a 404 error (document not found) error for the user, but there is no indication of that in the summary report. It may be useful to add a routine that labels such nonexistent pages in the reports. Frequently occurring errors could then be remedied by the system (e.g., most BLS page names use .htm rather than .html extensions and it may be useful to provide a filter that treats .htm and .html requests equally.

misc.txt This file contains a variety of summary data. It was not considered in this analysis. For December, the file was 185K.

hosts.txt This file contains statistics on machines accessing any of the BLS servers broken down by domain.

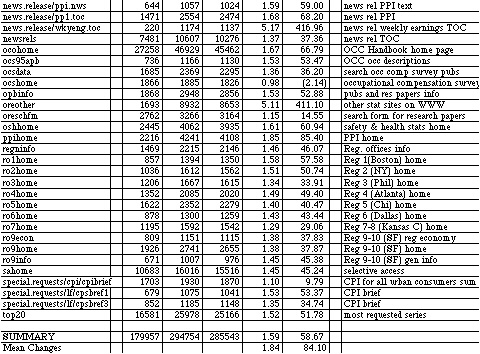

Sets of these files were obtained from BLS for the months of December 1996 and March 1997. These summary reports were used to determine which pages get the most activity, what types of keyword searches were conducted, and how many different hosts accessed the site. A comparison of summary usage was made between the two periods to determine whether there were changes in usage patterns.

2.2.6.2 Sequential Log Analysis.

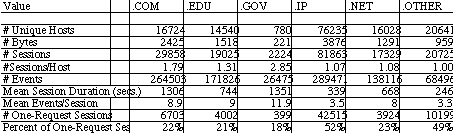

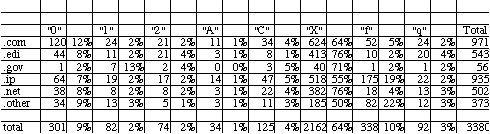

To investigate sequential patterns of use, one month's BLS raw transaction

logs (October 1996) were processed using the following procedure:

1. Transfer log file. The raw server log file was transferred via FTP to a Sun workstation at the University of Maryland.

2. Develop C programs to separate the raw log file into files in separate directories for different domains (com, edu, gov, IP, net, and other), delete GIF transfer requests, and to segment files into sessions. We chose a one-hour inactivity interval (between requests made from the same address) as the bounding condition for session segmentation. This decision needs empirical validation in future work.

3. Develop coding scheme to map specific BLS page addresses to the event codes We planned to use the Sequence Statistical Package to look for patterns in the data. Sequence limits event codes to a single character. Based upon our experience with the structure of the BLS site and examination of the summary statistical data for HTML requests, we developed a 57 code scheme for BLS pages and other states such as cgi requests and other requests. The coding scheme is presented in Table 2.2.6.1.

Table 2.2.6.1 BLS Coding Scheme

Each "session" will consist of the following:

sequence size, cluster, agreement, startdate, ID, domain, month,

day, carriage return Event1, Event2, .... Event N, carriage return

All sequence elements are delimited by spaces. If any sequence exceeds

255 characters, a carriage return is used as line continuation in place

of a space.

sequence size is the number of events (moves/pages) in the sequence

cluster is always 0

agreement is always -1

startdate is 0

ID is a whole number between 0 and 999999 identifying the sequence

(based on file name or IP address?)

domain is a whole number between 0 and 125. 1=ip address, 2=.edu, 3=.com,

4=.gov, 5=.net, 6=other country

month is a whole number between 0 and 13

day is a whole number between 0 and 32

Event is a single character code from list below followed by a forward slash (/) and the number of seconds that have passed since the beginning of the sequence; e.g., F/146 means occupational handbook home page 146 seconds into the session. Thus, first event will have time code 0, and the time spent in state S will be difference between time code for S and S+1.

Sequence event CODE URL Page

0 GET /blshome.html main menu

0 GET / [blank entry] (i.e., "GET /HTTP/1.0" 200 3390 has no path,

is the home page default)

1 GET /datahome.htm data

2 GET /eag.table.html economy at a glance

3 GET /cgi-bin/keyword.pl keyword search

4 GET /proghome.htm surveys and programs

5 GET /opbhome.htm publications

6 GET /regnhome.htm regional info

7 GET /infohome.htm BLS info

8 GET /orehome.htm research papers

9 GET /feedback.htm feedback

A GET /top20.html most requested series

B GET /sahome.html selective access

C GET /newsrels.htm news releases

D GET /cgi-bin/srgate* series report

F GET /ocohome.htm Occup. Outlook Handbk

G GET /opbinfo.htm publications

H GET /ro1home.htm I-Boston

I GET /ro2home.htm II-New York

J GET /ro3home.htm III-Philadelphia

K GET /ro4home.htm IV-Atlanta

L GET /ro5home.htm V-Chicago

M GET /ro6home.htm VI-Dallas

N GET /ro7home.htm VII&VIII-Kansas City

O GET /ro9home.htm IX&X-San Francisco

P GET /blsmissn.htm mission statement

Q GET /oreother.htm other stat sites

R GET /orefell.htm fellowships

S GET /blsorg.htm senior mgmt

T GET /inthome.htm international training

U GET /prohome.htm procurements

V GET /oreschfm.htm search BLS info

W GET /hlp* any help

X GET / missing or ambiguous entry

Y GET /cgi-imagemap/* any image map selection

Z GET /all other codes not listed

a GET /cgi-bin/surveymost most req series navigation

b GET /cgi-bin/surveymost?r* most req series choice-region

c GET /cgi-bin/surveymost?* most req series choice-other

d GET /cgi-bin/dsrv* selective access choice

e GET /*_warn* most req series or sel access warning

f GET /news.release/cpi* newsrelease cpi

g GET /news.release/disp* newsrelease disp

h GET /news.release/ecec* newsrelease ecec

i GET /news.release/eci* newsrelease eci

j GET /news.release/ecopro newsrelease econ prod

k GET /news.release/empsit* newsrelease empsit

l GET /news.release/laus* newsrelease laus

m GET /news.release/ppi* newsrelease ppi

n GET /news.release/prod* newsrelease prod

o GET /news.release/wkyeng* newsrelease

p GET /news.release/ximpim* newsrelease

q GET /special.requests* econ at a glance graphs & other special

reqs

s GET /cgi-bin/cocsearch.pl occ handbook keyword search

t GET /oco/oco* occ handbook other

u GET /emphome.htm occ handbook employment projections

v POST /cgi-bin/dsrv* Requests for selective access

w POST /cgi-bin/surveymost* Requests for series

x POST /* Other requests

Notes:

* in a URL is a wildcard character for one or more characters in both

pre and post positions

A single code for all types of help (hlp* is coded to W)

A single code for all "other" pages (coded to Z)

A single code for all clicks on menu images/icons (cgi-bin/imagemap/*

is coded to Y)

A single code for all selective access GETs (GET cgi-bin/dsrv* is coded

to d)

A single code for all selective access POSTs (POST cgi-bin/dsrv* is

coded to v)

A single code for all most requested series GETs (GET cgi-bin/surevymost?*

coded to b)

A single code for all most requested series POSTs (POST cgi-bin/surveymost*

is coded to w)

code 0 used for 2 entries

code e has left and right truncation

code x must be checked for AFTER codes v and w

The Sequence Program option used in the program requires that

each event is a single character code from list below followed by a forward

slash (/) and the number of seconds that have passed since the beginning

of the sequence; e.g., F/146 means occupational handbook home page 146

seconds into the session. Thus, the first

event will have time code 0, and the time spent in state S will be

the difference between the time codes for S and S+1. The coded record for

a sample session look like this:

1/0000 Y/0019 A/0020 c/0096 c/0113 c /0132 Y/0213 C/0213 X/0272 X/1015 0/1065 Y/1085 3/1086 X/1096 X/1120 X/1227

For each session so coded, header information was added that includes: ID (a unique number assigned incrementally as processing progressed--a number was required as Sequence does not allow alphanumeric variable values); domain code; month, day, and total time of the session. The Sequence Program automatically adds a value for the number of events in a sequence.

4. Develop C program to map raw log session files onto the coding scheme. This program was then used to create a file for each domain category that could be read by Sequence.

5. Use the Sequence program to explore usage patterns, i.e., sequential analyses rather than summary analysis.

This methodology was created specifically for the BLS site. We have attempted to make the procedure generic for any site and have used modular coding for the C programs to make it feasible for a different coding scheme to be substituted. Much of the effort went into processing the data for importation into the Sequence program. As other sequential statistical packages become available, it may be beneficial to reconsider the coding scheme if more descriptive and extensive codes are possible (e.g., using the IP address as identifier rather than an integer, coding hundreds of pages rather than 54, etc.). Nonetheless, we believe that BLS can adopt the summary log analysis techniques immediately and begin to use the sequential analysis techniques to better monitor and manage the site.

2.3 Summary and Recommendations

As this section of the report has detailed, the methods used in

this study were exploratory in nature. The employment of these methods

enabled us to further our understanding of the research questions we asked

as well as of the appropriateness of these methods for general use in this

context. Given the methodological understandings developed, we believe

that the methods we have employed are useful for website evaluation, and

should be easy to adopt and extend for each particular website. Thus we

recommend:

3 The Fedstats Website: Findings, Analysis, And Recommendations

This section of the report concerns itself with the data collection and analysis activities specific to the FedStats Website. It reviews the data collection activities, rationales for their use, presents findings from each activity and a summarized list of key findings, and discusses the implications of these findings for our understanding of users and usage of statistical data in electronic format, methodological aspects, and system design.

3.1 Data Collection Activities

In section 2, the data collection activities employed throughout the study were summarized, including those specific to the FedStats site. Details about the methods used may be found in that section.

Overview of and Rationale for Methods. The data collection methods employed during the investigation of the FedStats site were designed based on several features of the FedStats project. When the study began, FedStats was not available for the public (in that its availability had not been announced) and thus the study team had no set of site users from which to gather data. Thus we relied on the insights and expertise of the FedStats task force to help us understand the goal of the site, the potential users, and significant system design issues. We met with the Task Force and also surveyed them via an electronic questionnaire (Appendix 2-2).

Recognizing that staff in the various agencies represented in FedStats already worked extensively with the public, addressing queries via email, phone, fax, and mail, we gathered data from these staff about existing users and user tasks via an online questionnaire (Appendix 2-3) in order to use the results to extrapolate to potential users of the new site. An additional strategy aimed at developing an understanding of possible site users and their tasks was the use of focus groups conducted with users/intermediaries of federal statistics. We specifically attempted to identify people who not only were probable users of these statistics but also who had specific job related responsibilities of working with other users who had need for statistics. Thus focus group members included librarians, analysts at research agencies, etc.

Prior to the site's official availability (May 22, 1997), we also performed a series of usability tests with potential users of the site in order to provide specific system design recommendations.

In the last month of the project after the site was officially announced and publicized, we were also able to gather some data about actual site use via the online comment form on the site. While we weren't able to do a detailed analysis of these comments, we were able to form an impression of the types of questions/comments offered by these early users.

These activities were designed to answer the study questions for the FedStats site. As a reminder, these questions were:

1.What categories of information seekers use (or would use) the site?

2.What are the tasks (or goals) in which these information seekers

are engaged?

3.What strategies are employed by information seekers as they use the

site?

4.What are the design implications for the site of answers to the previous

questions?

In reviewing the findings and their implications, it is important to bear in mind the changes that occurred in the site during the course of the study. Table 3.1.1 coordinates specific data collection activities, with site changes which impact results of the various activities.

(INSERT TABLE 3.1.1 HERE)

3.2.1 Interviews with Members of the FedStats Taskforce. The online questionnaire was distributed to the FedStats taskforce in January 1997. All members of the taskforce responded, with 2 members indicating that they did not interact with the public and were on the taskforce for specific reasons and thus were not able to answer the questionnaire questions. Verbatim responses (in some cases slightly summarized) are presented as Appendix 3-1.

A wide variety of audience types for the site were suggested by the taskforce members in response to the question: What audiences would you consider to be primary groups to be served by OSS [One Stop Shopping -- the earlier name of the FedStats site]? The many types mentioned can be grouped into several major categories. These are: the general public, or perhaps more specifically people who are not regular users of statistics who are looking for statistics for personal, rather than work reasons; business users; the media; government users (down to the local level); students and teachers; researchers; staff in Federal statistical agencies; and staff in libraries/museums and other non-profit organizations.

In response to the questions, What activities do you anticipate them engaging in at the OSS? What questions/tasks do you think users will bring to OSS? there was again a wide range of answers but a set which could be grouped into several categories. These categories of use were: general topical questions, questions about whether data are available, questions looking for a specific number, questions to prove/disprove a point, questions with a geographic focus, and more broad questions such as requesting general education or referral.

The remainder of the questions on the questionnaire were intended to tap into the taskforce's perceptions of the site goals, site organization and structure, and the issues which might need to be addressed as the site developed.

Questions 3 and 4 on the questionnaire asked respondents to comment on the types of information that should be accessible via the site (q. 4) or on the site (q.3). Since the site has the primary goal of being a locator system, a distinction is possible between data actually on the site versus information available through the site. Not surprisingly, since the taskforce has been the architect of the site, there was a general consensus that data on the site should be limited to links to information, general information about Federal statistics programs and various searching and navigation tools, while the individual agency sites would be where actual statistics and associated metadata would be available.

Questions 5 through 8 asked respondents to comment on site design, asking for possible suggestions for additional organizational structures for the site (q. 5), the best thing about the site (q. 6), the worst thing (q. 7) and possible improvements (q.8). Respondents provided information related to all these questions at various places in the four questions so both here and in the summarization (appendix 3-1), these have been reorganized.

The two answers provided to question 5 were to include keyword searching of the various agency sites, as well as keyword searching of the FedStats site.

Each respondent highlighted different best and worst things. Best things about the site included the ability to get feedback from users, the convenience of the comprehensive list of agencies, possibility of creating a greater awareness of the Federal Statistics Program, providing a service to citizens, and the A-Z subject function of the site. Worst things included need to provide access to more than the Statistical Abstract of the U.S., lack of a significant feedback mechanism, development and maintenance time, the perception in some agencies that the FedStats site is a threat, lack of inclusion of the Federal Reserve, slow speed, and a potential for inadequate numbers of support staff.

Related to these comments, were the responses to the question about how to improve the site. A wide variety of suggestions were made. Mentioned by several respondents were: mechanism to collect user feedback, ability of site to parse complex user queries, tools that would allow users to integrate data across agencies and query by topic, historical or geographic focus. Also mentioned were the provision of a discussion list, analysis of usage statistics, customized extractions, include definitional, methodological, and analytical narratives along with the data returned in response to a query, access to more (and more current) statistics, user input into site organization, and working with agencies to develop standard practices of dissemination.

Throughout the questionnaire (but most particularly associated with responses to questions 5-8) were a number of comments concerning issues that organizers (and various agency personnel) may need to address. One person commented that he various taxonomies used by agencies will make it difficult to guide users to the most appropriate data sources. The same respondent indicated that the different geographic splits, different definitions of occupations, minorities, etc. will also make it difficult for users. Another respondent indicated that the site may serve to increase awareness of those differences. One person indicated a concern about the amount of feedback the taskforce will be able to get. Finally, a concern was mentioned about the amount of resources necessary to maintain the site (particularly if it remains largely manual maintenance).

3.2.2 Online Questionnaire to Agency Staff. During January 1997, staff in various agencies represented on the FedStats site received an online questionnaire. Potential respondents (and their email addresses) were identified by members of the FedStats taskforce. A total of 15 specific names were provided to the study team, 11 of these people responded to the survey. The questionnaire design followed the interview schedule used with the BLS/CPS staff with the addition of several questions specific to the FedStats site. The survey questions and answers are reported in Appendix 3-2. Respondents were asked to identify the agency in which they worked. Of the 11 respondents, 2 worked for the Bureau of Economic Analysis, and 3 each worked at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Science Foundation, and the National Energy Information Center.

In response to the first question, many types of users were indicated. A review of these answers led to a sense that the same types of users were being mentioned by these respondents as we had found in previous activities. Thus, respondents mentioned researchers, students and teachers, business users, the media, government users, the general public, staff in Federal statistical agencies, librarians, and staff of non-profit organizations. New types of users included foreign persons (both researchers and government users), statisticians, international research and trade organizations, and job seekers. There was only a small overlap in specific terms used in the answers. Respondents either used different terms for the same group or provided different groups.

Question two asked respondents to indicate the type of questions asked. Again a wide range of answers was provided. These responses could be categorized into requests for:

Some specific questions were given as responses to this question such as:

survey numbers broken down by industry (NSF)

The following question asked about the tasks in which users were engaged. Not surprisingly the range of responses was again large. There were approximately 33 answers which were grouped into 11 slightly more general categories as follows:

When asked to consider what groups might not being making use of their data but could, in general, the respondents who answered the question indicated that while there probably were some groups, the reason for non-use could be lack of awareness or knowledge of how to use. Some specific groups were mentioned such as students, older Americans, and business people.

A series of questions was asked to better understand the analysts' jobs. The first question asked about what kinds of information they were responsible for providing help. The responses ranged from "everything provided by BEA" to specific program areas within an agency (e.g., electricity and nuclear related information). Some respondents mentioned that they provided information about use of technologies.

Information about the tools analysts use was also solicited. Agency databases and publications, directories, the Internet, and industry sources were all mentioned. Analysts used internal information, other government information, and external sources.

When asked how the public contacted them, not surprisingly the respondents indicated mail, phone, fax, email, in-person, and website feedback. Some differences in the use of the different modes of communication were noticed by analysts. Some channels are used more frequently than others. All analysts who answered the question reported the phone as the primary mode of contact. There was not much overlap in the answers.

General comments offered by respondents about their job centered on their roles as intermediaries and public service staff. One person indicated that one tries to remain polite, accommodating, and helpful. Interaction with customers also led to more specifically defined queries. One person expressed concern that the agency wasn't able to adequately address all the questions "out there."

While only one person had used the FedStats site at the time of the questionnaire, a range of suggestions were made. These were (all suggestions included):

As with the responses to the online interviews, the respondents in the focus groups identified a wide range of user types that they helped. The categories of user mentioned included: the general public ("all kinds of users of government information" as one respondent put it) business users, students and teachers, and researchers from federal agencies (in particular BLS and the Census Dept.) and non profit organizations. In addition to these categories, several unique categories were mentioned in the focus groups. In focus group 2, there was agreement that many users could fit into a categorization of "sophisticated (statistics) users with technical skills, sophisticated users without technical skills, non-sophisticated users without technical skills, non-sophisticated people who want to get sophisticated." In all the focus groups, at least one person responded only to requests from members of the organization of which he or she was a part. Two other categories of user mentioned in the focus groups were people who had been referred to them from somewhere else or people "who don't know where to turn."

These users were reported as having a wide range of needs and a wide range of statistics they wanted with respect to those needs.

Needs mentioned were:

comparisons (2 groups),

locator information (e.g. which person should I call, what agency has

X data), market intelligence and trend tracking (3 groups),

determination of how many/how much of something (3 groups),

learning about occupations and career opportunities (3 groups),

looking for relocation information (3 groups),

planning tasks,

writing grants (2 groups),

doing reports,

estimates of statistics or projections,

assessing the economic well being of state or region.

The variety of topics on which statistics were wanted was also varied according to the groups. Categories of topics include:

The respondents reported that they and their users wanted data from a wide variety of Federal Agencies including agencies affiliated with the Federal Statistics Program as well as other non-affiliated agencies. In addition, they also relied on commercial providers of data (if they could afford to), as well as locally produced or concatenated sets of data. Respondents had a wealth of sources at their disposal. In the first focus group, for example, everyone had used everyone else as a referral in the past. These respondents were generally well tied to the data collection and dissemination agencies at the regional and state level. Some were not, however, and at least one person thanked the interviewer for holding the focus group because she had learned so much about what other agencies had available. They seemed to employ these local connections quite often in response to client needs.

Topic, geography and time were dimensions of statistics that seemed to be important to the focus groups in terms of distinguishing between user needs. The groups indicated that many of their users wanted local data and would take higher aggregations (state, region, national) if local data were not available. The need for current as well as historical data was mentioned and there was some suggestion made that this was one way to distinguish between questions.

The focus groups also reported on user expectations. These can be summarized as "users expect to be able to get the exact information they want in the exact form that they want for the current year." and "users will frame queries in terms of what they think they can get rather than what they actual want."

As intermediaries, the respondents reported on activities they performed for their users. They may find specific data for people, help people use data (either in terms of technical aspects such as downloading or content aspects (such as metadata, methodology, or interpretation), identify people/agencies or other sources to direct the person to, educate their users about data collection strategies employed and how statistics were calculated, or analyze data for users.

The focus groups were asked to consider what a site designed to support the location and access of statistics might include. An extensive assortment of suggestions was made. These can be categorized into several areas (all suggestions are listed):

look of pages: uncluttered, simple

The groups also mentioned issues that made using statistics challenging. The differing data collection methods, definitions and formulas were recognized as possible barriers to easy use by the general public and to aggregating data across agencies.

3.2.4 Usability Tests. Three usability tests of the site were conducted in March and May 1997. Details of the tests are described in the Methodology section of the report. Summaries of data collection instruments are included as Appendix 3-4. Analysis of the results included tabulations and calculation of associated means for the usability questionnaire, summarization of the answers and comments from the scenario worksheets, and the searching of the transcripts for information related to the research questions and for the identification of other important themes related to site use and usability. As was previously stated, respondents' use of the system itself was not recorded, thus we present no findings related to actual use of the system. By asking respondents to comment on their experiences generally (rather than recording their keystrokes), we are able to gain a more general picture of their use and higher level system design recommendations.

3.2.4.1 The Usability Questionnaire. The usability questionnaire asked first about frequency of use of the Web in general and for finding statistical information. 10 of the 17 participants used the Web at least once daily and 5 used it at least once a week. Only 2 respondents used it less frequently. Everyone had used the Web at least a few times to look for statistical data but only 4 respondents used in on a daily basis. Potential respondents were screened for web use (only those with web experience were included in the sample)and for some knowledge of statistics though not for usage of the Web for finding statistics.

Table 3.2.4.1 reports the results of the usability questionnaire. Respondents reported perceived success in scenario completion. The averages of the scores were above the scale's midpoint (3) except for group 1's results for the third (individually chosen scenario). This result may be due to the fact that the search feature was not operational on FedStats at the time of the test. Average scores on overall reaction to the site measures, differed greatly between group 1 and groups 2 and 3. As a group, Group 1 gave the site higher scores on all measures, in some cases markedly so. For example, on the terrible/wonderful scale, Group 1's average was 6.29 while Groups 2 and 3's averages were 3.5 and 3.833 respectively. Group 1's score is above the midpoint on the numerical scale (1 to 9) while 2 and 3's are below. This pattern holds for all the measures in this section of the questionnaire.

Average scores are more consistent across the three groups in the section on screens. All average scores on all questions are above the midpoint of the scale and range from a low of 6.25 (Group 2 - helpfulness scale) to a high of 8.5 (groups 2 and 3 --ease of returning to previous screen scale).

Terminology questions also had Group averages above the midpoints on all scales for all groups and again are reasonably consistent across all the groups. The only area where less satisfaction was reported was in error messages (with averages ranging from 4-5). However, many respondents marked "not applicable" on that question perhaps because no error messages were received.

Consistency is also evident in the final section of the questionnaire, questions related to learning the system. Group averages were above the midpoints on all scales for all groups, ranging from a low of 6 (group 2 - getting started scale) to a high of 8.33 (group 2 - clarity of instructions scale) Aside from the anomalous results concerning overall reactions, the more specific measures indicate that respondents found the site usable. The low average scores for groups 2 and 3 on the overall measures are a bit mystifying given that higher scores on the other metrics and also given the addition, at that point, of the keyword search functionality.

Table 3.2.4.1: Results of Usability Questionnaire

| Averages | ||||

| Background Questions | 3/28 | 5/19 | 5/27 | Total |

| Please rate how successful you thought your search was for the information

in Scenario 1?

1-5 Scale Not at all successful/Completely Successful |

4.86 | 5 | 3.5 | 4.45 |

| In Scenario 2? | 4.71 | 3.25 | 4.33 | 4.10 |

| In Scenario 3? | 2.57 | 4 | 4 | 3.41 |

| Overall User Reactions to WebSite 1-9 Scale | ||||

| - Terrible/Wonderful | 6.29 | 3.5 | 3.833 | 4.76 |

| -Frustrating/Satisfying | 5.57 | 3.5 | 3.67 | 4.44 |

| - Dull/Stimulating | not asked | 2.67 (1 NA) | 3.9 (1 NA) | 3.29 |

| - Difficult/Easy | 7.57 | 4 | 4.33 | 5.59 |